As 2020 toppled into 2021 like dominos across the timezones, January 1 marked the EOL event for Flash, one of the most idelibly controversial and significant internet products.

What was Flash? A relic of the early web, trashed by Steve Jobs, wracked with security holes and inescapable performance faults? Or an amazingly holistic motion graphics and programming tool that bridged the divide between creative and technical workflows and broke down barriers to participation in game development, animation and web design? Both and other? Either or neither? The player versus editor dialectic?

“History is overdetermined,” flies the catch-cry of our emerging era. With this heightened sense of collective awareness that society and culture are open systems, even asking “what the fuck just happened?”–the basic polymer starch of the retrospective essay—already presupposes a historiographical conundrum. Whose story is it to tell? Because what the fuck just happened with Flash spans 25 years concurrent to the entire history of the modern web and videogames but its influence also spills into broadcast pop culture, from Peppa Pig to Aqua Teen Hunger Force.

Particularly striking in 2021 is the contrast between Flash’s early years of chaotic and creative growth on the web, and its decline over the past decade. Sure, it was always around somewhere, still widely used, but it just wasn’t culturally or technically relevant.

Decadal thinking can be a tiresome and misleading trench to gaze out of. I’m not here to mount a defence of the English-speaking world’s obsession with parcelling Zeitgeisten into cultural units of ten, but there is a meaningful underlying pattern to the 2010s. The steady dissipation of Flash’s influence on design culture and its technical obsolecence is not an isolated curiosity in the history of media and technology. It’s set amongst something bigger. Something distinctive, weird and transformative that took place over the last ten to twelve years. My conceit here is not chronology, but to instead use the span of this past decade as a magnifying lens to focus enough heat to set alight an epic catalogue of how we got here.

The medium is the message and the massage is massively stimulating networks in the fatty tissue of the human brain as directly and precisely as possible through light, sound and haptic signals. But this is just the user interface loop.

The anatomy of planetary-scale computation can be understood as a single stack, reaching down from users—both humans and machines—and interfaces to enclose software, urban infrastructure and the labour pools and resources of the whole earth, from supply chains transforming conflict minerals into microprocessors and sensors, to massive data centres hosting server arrays with hardware idling in a high power state waiting to serve the next request, whether it be an audio bark flung into a buffer by Alexa or Siri, a fumbling finger flicking a touch screen, or a bundle of parameters generated by a decision algorithm.

This is the digital infrastructure we’ve wrought in the early 21st century. A cybernetic hyperobject merged by accident and design that wraps—and warps—the whole world, challenging traditional notions of sovereignty and control.

The past decade has seen a massive rupture and break with pre-existing research traditions and notions of the web. All the components of planetary-scale computing are connected by common threads of universal internet and web protocols but the emerging applications of artificial intelligence, predictive analytics and the Internet of Things are worlds apart from the original ambition of the web as a vast horizontal and vertical library of pages forming a global system of bounded knowledge contexts.

At the technical level, this transition was anticipated by the web’s early architects. Their impetus was the problem of the web’s anarchic scalability leading to the later realisation that instead of referring strictly to pages, URL addresses could refer to any kind of resource representable as a noun. Combined with insights into encoding data using markup languages, all this unexplored potential gave rise to the idea of a Semantic Web of machine-readable knowledge bases, enabling the possibility of remote agents ‘reasoning’ over data. Though many people guessed at the transformative economic potential of computing at this scale, they did not comprehend its entanglement with social and cultural forces.

I have a dream for the Web in which computers become capable of analyzing all the data on the Web—the content, links, and transactions between people and computers. A ‘Semantic Web’, which makes this possible, has yet to emerge, but when it does, the day-to-day mechanisms of trade, bureaucracy and our daily lives will be handled by machines talking to machines. The ‘intelligent agents’ people have touted for ages will finally materialize.Tim Berners Lee, 1999

Today, the W3C’s formalised Semantic Web project is often remembered as a cul de sac initiative to develop AI reasoning systems. Despite many of its foundational ideas becoming established technology standards, the logic and proof layers never came together in a plausible way that could adequately address the inherent information bias problems of allowing automated systems to ingest live data from the internet and make decisions without human intervention.

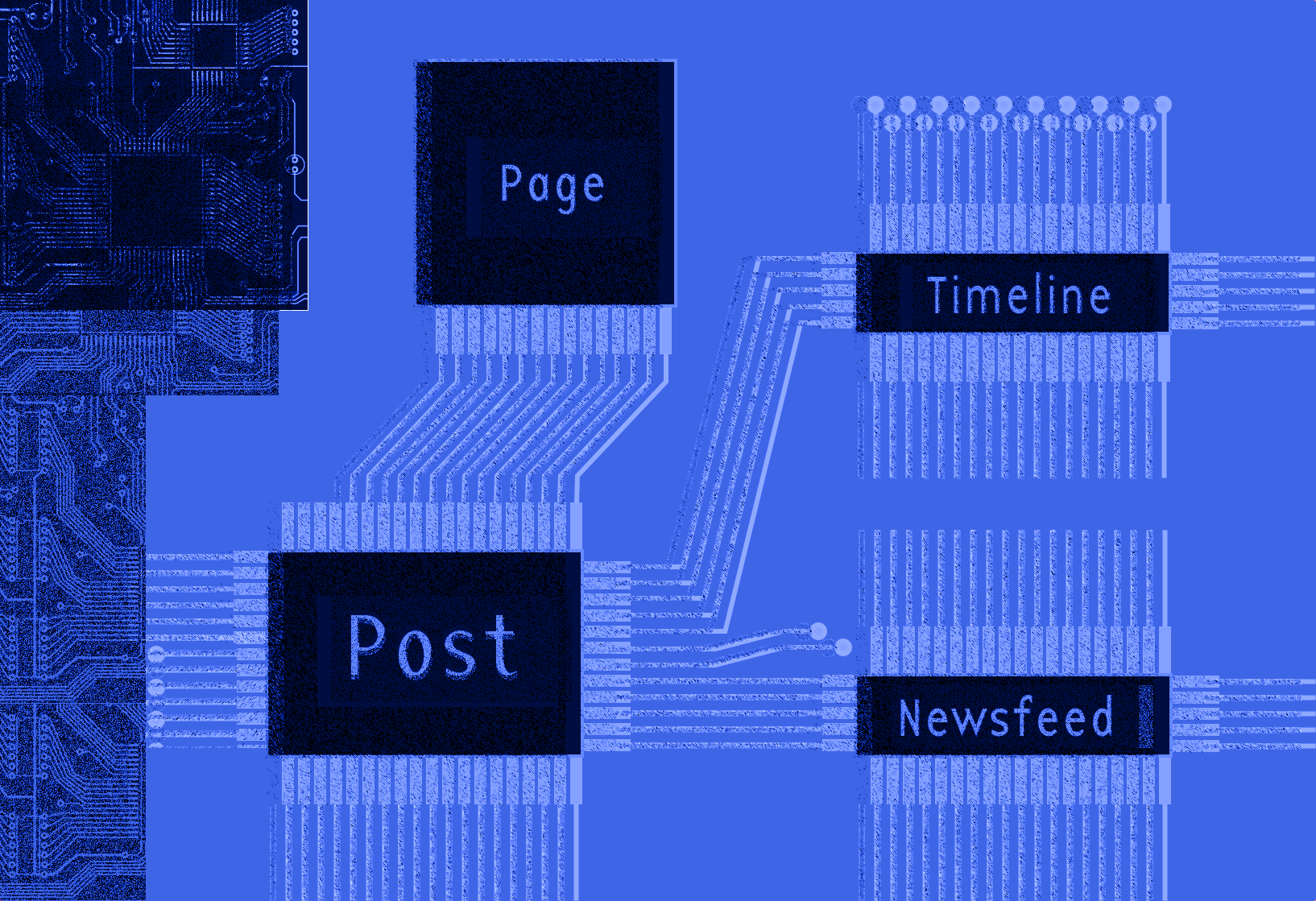

Enter Facebook, which reared up in competition to challenge Google’s mission statement to “organise the world’s information and make it universially accessible and useful”. With a dubious emphasis on ‘real names’ representing a single unifying identity, Facebook skipped over everything the Semantic Web community had done and went straight to the end result: a proprietary corporate-owned social graph with an internally consistent ontology linking billions of nodes representing people, places, objects, events and ideas.

In the early years of the web—before it merged with the concept of the internet and ‘apps’ in the popular imagination—clicking was strongly associated with metaphors of spatial transport. Hyperlinks embodied the idea that knowledge is associative and densely connected. An ocean to navigate rather than a fixed mosaic of facts or commanding scripture. A hyperlink could take you to another section of a document, a footnote, a new page, or a totally new website. Forging these hyperlinks to enhance the experience and communicate ideas became an integral part of web design.

Facebook, Google, and other social media giants learned to quantify and harness these links as a currency of attention that could be used for ad targeting. They broke down their interfaces into curated slot machines delivering media objects to incentivise the production of clicks and wired the whole thing into gamified interaction loops. They built giant data centres beside hydroelectric dams and used the whole assemblage to put news media, creative industries and conventional politics on blast, while at the same time making millions of smaller businesses around the world utterly dependent on their services.

Perhaps the early Semantic Web researchers are extremely lucky their cumbersome attempt at automating the world through metadata has so rarely been implicated in the rise of monopoly control over the internet and all its problems that obtain. Or perhaps we all fundamentally misunderstood the lessons that were staring us in the face all along. For years, influential criticism of the Semantic Web discussed problems like uncertainty, inconsistency and deceit in theoretical terms before such problems became material and consequential at scale. The big question should never have been about whether or not to build the Semantic Web, but about how to mitigate such risks throughout all networked infrastructure and social media.

It was a terrible opportunity to squander. Digital redlining, networked disinfo and harassment campaigns, incitement of genocide, livestreaming murder and terrorism, to give just a short list of the most extreme outcomes. Moving fast, breaking things, optimising for individual engagement, amassing armouries of defensive patents and hit squads of government lobbyists has not led to the transcendant new forms of human organisation as promised by the Californian ideology in the late 90s and early 2000s. Instead, the fêting of harmful consequences as economic externalities is a reverberation of the same destructive practices of the 20th century tobacco industry, oil industry, agribusiness and friends. These patterns of market manipulation, hierarchical dominance and profit extraction are all too familiar.

What is the point of encasing ourselves in a planetary-scale computing grid? What is it for? For some, it’s the Promethean impulse to construct a global mind. For others, the desire to gaze into the horrifying abyss of humanity and communicate truth and beauty, ecstasy and despair. For others, it’s a crystallized exoskeleton of existing racism, imperialism, fascist tendencies, culture wars and Cold War logic—the latest eruption in the centuries-long struggle between indigenous existence, socialist commons and capitalist enclosure as models for how the world should be. For the billionaire class and their revolting conflicted political and economic servants, it’s a frontier of potential monopoly platforms, a manifold of markets to manage, a registry of the working population to exploit and extract from. For partisans and nation state operatives, it’s an enormous threat to irreducible borders and absolute control that also presents enormous opportunities for public relations, intelligence collection and active measures.

When the Arab Spring kicked off in 2010 and 2011 with waves of networked protest, civil unrest and anti-government uprisings, Western intellectuals celebrated the role of social media as a catalyst for bringing down authoritarian regimes. This was cannily exploited by the social media companies themselves who used free speech absolutism as a marketing tool, drawing people all over the world into a hall of mirrors censorship debate that still rages today, with few recognising the underlying motivation of these companies to maximise profits by reducing moderation and community management to the absolute minimum they can get away with.

Less than three years after Tunisian fruit seller Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in defiance of government and police repression and the Occupy movement confronted financialised inequality, Edward Snowden staged his wild end-run to Moscow, leaking an enormous cache of secret documents from the CIA and NSA, revealing for the first time the extensive scope of FVEY mass surveillence and digital espionage programs.

At the time, the widely-reported contours of this document dump were around data collection, message interception, supply chain interdiction and global targeting capabilities through XKeyscore and PRISM. A disturbing lack of attention was paid to the underlying message of these documents as a whole—what they said about Western governments drifting towards authoritarianism and preparing for widespread civil unrest.

Within the sphere of American media influence, the Ferguson uprising in 2014 was a moment of mass recognition that what was happening on the periphery of empire was encroaching on the centre. Faced with the intolerable injustice of racially-biased paramilitary policing, the protests, riots and police brutality were livestreamed across social media, gaining solidarity from a global audience uniting around the Black Lives Matter movement. This was a powerful fusion of the compounding civil unrest predicted in the paranoid style by the Pentagon and security agencies. Just as with Occupy around the world—and with continuing protests and activism for the remainder of the decade—the American establishment’s priority was to defuse tension and disrupt the movement rather than committing to fixing anything, continuing its longstanding tradition of meeting the exercising of rights with force and violence.

In 2015, it still seemed inconceivable within the American technocratic mediasphere that Gamergate and the growing alt-right movement was a serious threat to liberal democracy. Inconceivable that Trump could even be nominated, let alone be elected. Inconceivable that Brexit would actually play out. Inconceivable that right wing authoritarian movements were gathering momentum in Eastern Europe, Brazil and other parts of the world. Inconceivable that social media was being torn apart with psyops, cyber warfare, organic harassment campaigns and vigilante justice. Inconceivable that many of these incursions were not only ordered by nation states but also privatised freakshows drawing from the focused obsessions of billionaire-funded subterranian culture war think tanks relentlessly pursuing election interference, culture jamming, active measures, influence operations and social impact investment strategies aimed at controlling political activism and popular culture.

Can you see the paradox here? Without social media we may not have this widening collective awareness of world historical injustice and the struggle for younger generations. But with social media, we swim against an inexorable tide pulling us towards anger, polarisation and reproduction of injustice. An impossible Escherian looking glass that is both a magnifying lens and a mirror converting the death drive into discourse.

Any exploration of the political dynamics of social media is at risk of yielding to the pressure gradients of reductionism and ideology. The right wing retort to anyone suggesting “We should improve society somewhat” is to attack the belief that society can be improved. Hierarchies and power are as-is and we can only solve for individual moral character. Therefore, social media systematically incentivises virtue signalling and cancel culture where wannabe social engineers and doctrinaire scolds clash for attention in a competitive social hierarchy. On the left, editorialisation has pinballed wildly over the past decade between social media as a ‘public square’ for civil society that gives a voice to the previously voiceless, and notions of a ‘techlash’, oftentimes launched from a deterministic explanation of social platforms exploiting vulnerabilities in human psychology to entice engagement through language replete with unstable referents of addiction, passivity and helplessness.

While there is some grounding for these claims in observed reality and personal experience, their reductionist limits become impossibly totalising positions. We are insincere tribalist caricatures. We are dopamine-hooked rats in a psych experiment. We are the ignorant marks of cognitive hijacking by Russians slamming insert moral panic buttons or Chinese pushers dealing digital fentanyl.

A basic problem with all these critiques is that they leave no space for actual details of the carnivalesque hellhouse of political culture depicted on social media, from Trump rambling about injecting bleach to historically significant revelations of racism, brutality and authoritarianism. A giant showcase of the complete lack of correlation between prestige and competence. A cavalcade of main characters beclowning themselves. Moments of photojournalism that become monuments with incredibly precise symbolic meaning. A living window on the absolute state of letting industrial corporations, nation states and billionaires run amok and the myriad of creative ways people are telling them to fuck off. Neither reducible to a mythic marketplace of ideas nor a mechanistic radicalisation engine.

The semantic web architects imagined utopian scenarios where medical patients would use intelligent agents to crawl the website of their clinic to organise a booking and automatically negotiate the transfer of funds and public healthcare or insurance approvals needed. Today, most users of the web don’t have the ability to launch personal AI assistants to run off and fetch things for us. Many users of the web don’t have access to public healthcare. The digital economy is run by a small number of monopolists who exist to extract and target our personal information, promoting utopian capitalism for users while maintaining dystopian command and control over workers. Our AI is secret algorithms that scan across large datasets to deliver up decisions about what content to show us or whether to approve or decline a request we’re making. Our information commons is a system of algorithmically-biased feedback loops of habitual grifting where creators are becoming radicalised by their audiences.

Rather than internalising all of this as the ‘digital dystopia’, I’ve come to think of it as what planetary-scale computing looks like in a capitalist consumer culture when that culture is coming to terms with the hellscape wrought by colonisation, the planetary scale of economic inequality, desertification, deforestation, poisoned landscapes, oceanic plastic gyres and the constant high volume gas emissions that define the material existence of so-called advanced economies.

Imagine that this market-driven planetary-scale computational supply chain colossus is a palantír (yes, I know). When you stare into the abyss of hegemony and see the arch-structure of authoritarian violence that has always been the foil to bourgeois democracy, the hegemon literally stares back. Even the experience of poverty and the digital divide offers no respite from these circumstances. A person may not be ‘extremely online’ in any of the senses of popular culture and intellectual history enumerated in this essay but there’s almost nothing they can do to avoid being tracked by GPS devices, credit cards, CCTV, urban infrastructure sensors, facial recognition systems and the decision algorithms of data-driven financialised debt traps. Increasing urbanisation around the world is absorbing more and more people into this dynamic of coercion and surveillence as it grows.

It might seem overwhelming but the survival of democracy as a form of cognition—the crucial alternative to decisions being made by market automata or hierarchical dictatorship—requires thinking the unthinkable about crises and learning how to route around them.

With the next few years locked in to a path of continuing pandemics, supply chain disruption and climate breakdown, we use words like ecocide and anthropocene as compression algorithms to zip up all the overdetermined, underdetermined and path dependent trajectories of action and inaction that made this world. We doomscroll, feeling like we’ve been sucked into a media gyre where everything happens so much and time is out of joint.

Giant social media platforms as outgrowths of the plantary scale computing stack fell into place somewhere between 2008 and 2012, circumscribing the web’s lost decade where the concept of the global library and information commons faltered and was pushed back by the growth of behaviourist nudges and predictive analytics.

None of the original ideas of the web as global library are obsolete. They’re as relevant as ever before. If there are four logics of anticapitalism, there are four directions for handling the monopolistic consumerist planetary-scale internet: taming it (through regulation), smashing it (how exactly?), escaping it (if only we could) or eroding it (and this, finally, is what the web is truly made for). There are many possibilities for life in capitalist ruins.

On the 1st and 2nd of January 2021, as death-of-Flash discourse rattled through the plumbing of Twitter—surfacing in my timeline alongside reports of a huge prison riot and protest against intolerable conditions in Aotearoa—I thought of my own weird history with this contentious bit of software. My very first paid graphic design job in late November or early December 1998 required me to apply a layout and typesetting template from the creative director to turn a directory of Word documents and Powerpoint files into an enormous 80 slide presentation in Flash3 with smooth vector animation. The client? Ara Poutama Aotearoa: The New Zealand Department of Corrections.

Theories of change that seek to transform the internet—or consumerism, capitalism, surveillence et al—must account for the complexities of our own personal entanglements with hierarchies of oppression and the abstract machines of markets and computation. The planetary scale of computing and supply chains transcends individual agency but isn’t reducible to purely externalised forces that do things to us from the outside or question-begging accounts of capitalist logic. We are load-bearing components of this infrastructure ourselves.

Most of the digital culture that was encoded in Flash has been lost and will never be recovered in archives. In hindsight, it’s easy to dismiss Flash as a technology failure, consigned to history as a long-lived but fatally flawed media protocol alongside other aborted assemblages like the Semantic Web and MySpace. Yet Flash changed culture in countless ways, pumping the reinforcing loop of big tech by enabling YouTube, FarmVille and a host of other apps that took us over the precipice, and also raising the bar for graphic design, typography and animation on the web, influencing the powerful capabilities of modern browsers.

In order to build a more resilient, adaptive and healthy media culture on this foundation, it is vital to reform and sustain the idea of the web as a garden of forking paths, index of cultural storehouses, ocean of knowledge to navigate at liberty. A library at the end of the world for solving the problems of our time, which we can use to temper, quell and route-around the worst impulses being acted out at scale across the internet right now.

I don’t want to insist that returning en masse to a design culture emphasising personal websites, explorable explanations, interactive narratives and zine-like forms of written and visual expression is anywhere near enough to process the weight of grief and loss so many people are experiencing, nor enough to save democracy, fix journalism, dismantle structures of oppression, end white supremacy, spur climate action, and so forth.

What I do insist is that all participatory media involves unavoidable creative and ethical tradeoffs. If we all spend at least some of our time chipping away at the problem of publishing long-lasting and durable things on the web, what we can create has vastly more emancipatory potential than the nihilistic and compromised defaults of the established order. This logic may seem obvious but it bears repeating as the emerging culture reclaiming the web is not necessarily so obvious or easy to define. It’s neo-webrings, small social networks, homebrew website clubs, working with the garage door up, screenshot gardens and the growing movement of creators removing analytics trackers and plugins entirely from their websites.

Huge challenges stand in the way, from Metcalfe’s law to our fluctuating individual capacity to cope with massive change amidst ongoing stresses and traumas of pandemicity and precarity. There are technological challenges too. The lost decade is not only the story of changing patterns of attention, media consolidation, and the reach of big tech expanding to the scale of billions of people. It’s also about stagnation in the development of popular tools for building the web. The death of blogging can not be separated from the decline of blogging tools and publishing software designed for non-experts. While easier than ever before to sign up to a corporate platform and post, the status quo for managing a personal website now involves a dizzying accumulation of programmer-centric complexity that obfuscates the basic purpose of publishing. It’s no accident people often hear more about ‘learning to code’ than about making real things that have meaning.

If the choice of our time is the politics of social cohesion versus the politics of fear, in the English-speaking world, these questions cannot be separated from much older questions about colonial nationalism, the role of the state and the relationship between politics and economic theory. The anti-expert wave has broken and crashed on the shore. The long-theorised and oft-feared native American fascism is no longer a spectre on the future horizon but a revealed set of feelings and political demands that are intrinsically connected to the internet and being online in a cultic state.

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the corroded and poorly-reinforced position of liberal democratic assumptions about society and collective purpose. Things that were once taken for granted—that democratic governments would care about citizens not dying and take obvious steps to prevent it—no longer seem certain.

Transformative political change requires collective action that uses democracy as a forcing function to move whole systems towards phase transitions. We cannot tinker and adjust our way to safety and security without perpetuating the existing system dynamics. Understanding these dynamics requires the situational awareness to accurately percieve recent intellectual history as responding to the tensions and contradictions of actual events, rather than returning to the flawed abstraction of society where politics, economics and culture are imagined as separate responsibilities.

How can we transcend a media culture of linear accumulation, temporal disaggregation, erasure of power, and engagement-driven amnesia to process and contextualise what the fuck just happened? Questions of system dynamics and situational awareness are tied up in our current cultural neurosis, endlessly worrying about the internet being captured and how future historians will know what to think about all these mistakes rendered in live media.

Making the subtle shift in our imagination and perception towards (once again) thinking of the web as a universal library is a way out of this neurosis. Simply having a website is sufficient to help push the rudder of the web back to its original heading but in order for this vision of the web to have meaning, we must grasp its greater purpose in charting the plurality of paths to a less fucked future.