There’s a curious similarity to many games depicting the ocean in how they reduce vast expanses of water to flat blue surfaces on a map. Players control vehicles that travel over it. Sometimes they can dive below it. Frequently, the ocean is treated as a grid where every area is alike.

For the Polynesian voyagers who first reached Aotearoa and Hawaii and built a civilization spanning the ocean like a continent, this flattening to uniformity circumscribes the great tragedy of colonialism. To peoples of the Pacific, the ocean is not a space that separates but a network of pathways that binds everything together: a living seascape of currents, wave diffractions and migrating animals, every bit as textured and palpable as dry land.

It’s probably unsurprising that so many games are oblivious to this. Modelling the ocean as a blank surface might be a reflection of industrial society’s reductive thinking around the ocean being merely a ‘body of water’. Waste is dumped into it. Resources are extracted from it. ‘It’ is rarely depicted as a dynamic living whole.

In Other Waters charts a new course for videogame representations of oceans. The first published game by Jump Over the Age (the solo studio of London-based artist and game designer Gareth Damian Martin), it draws from a wealth of familar game design elements and science fiction tropes but puts it all together in a form that’s totally unique.

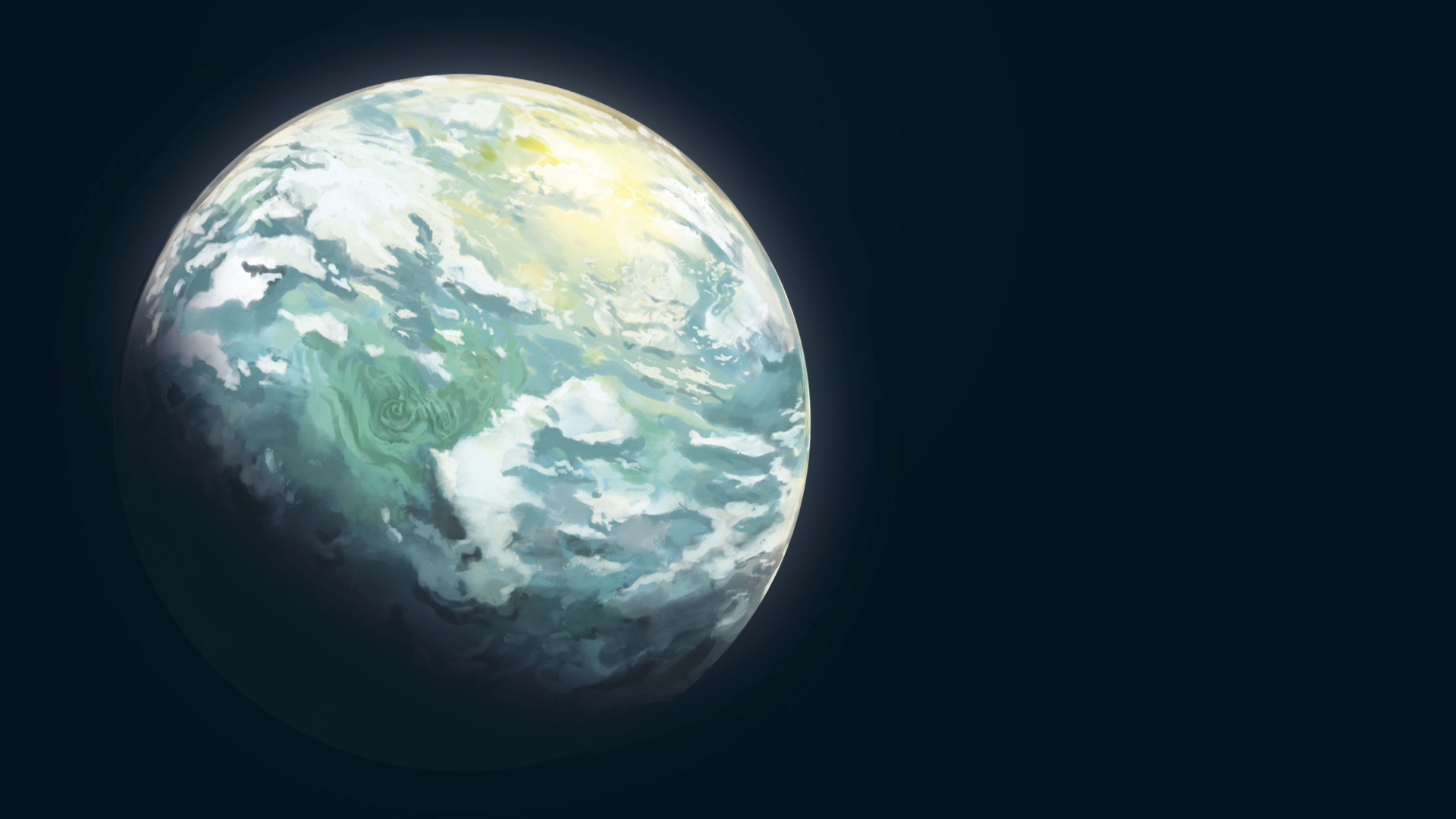

Set on the watery exoplanet Gliese 667 Cc, the story follows xenobiologist Ellery Vas who gets stranded after answering a distress call from her former partner Minae Nomura. The game opens with the player waking up on the shoals of an alien reef embodied as an AI-powered diving suit. Instead of taking on the role of the lead character herself, the player becomes an AI assistant for Ellery, using the limited tools available as the exosuit to launch communication channels and sensory links to the outside world.

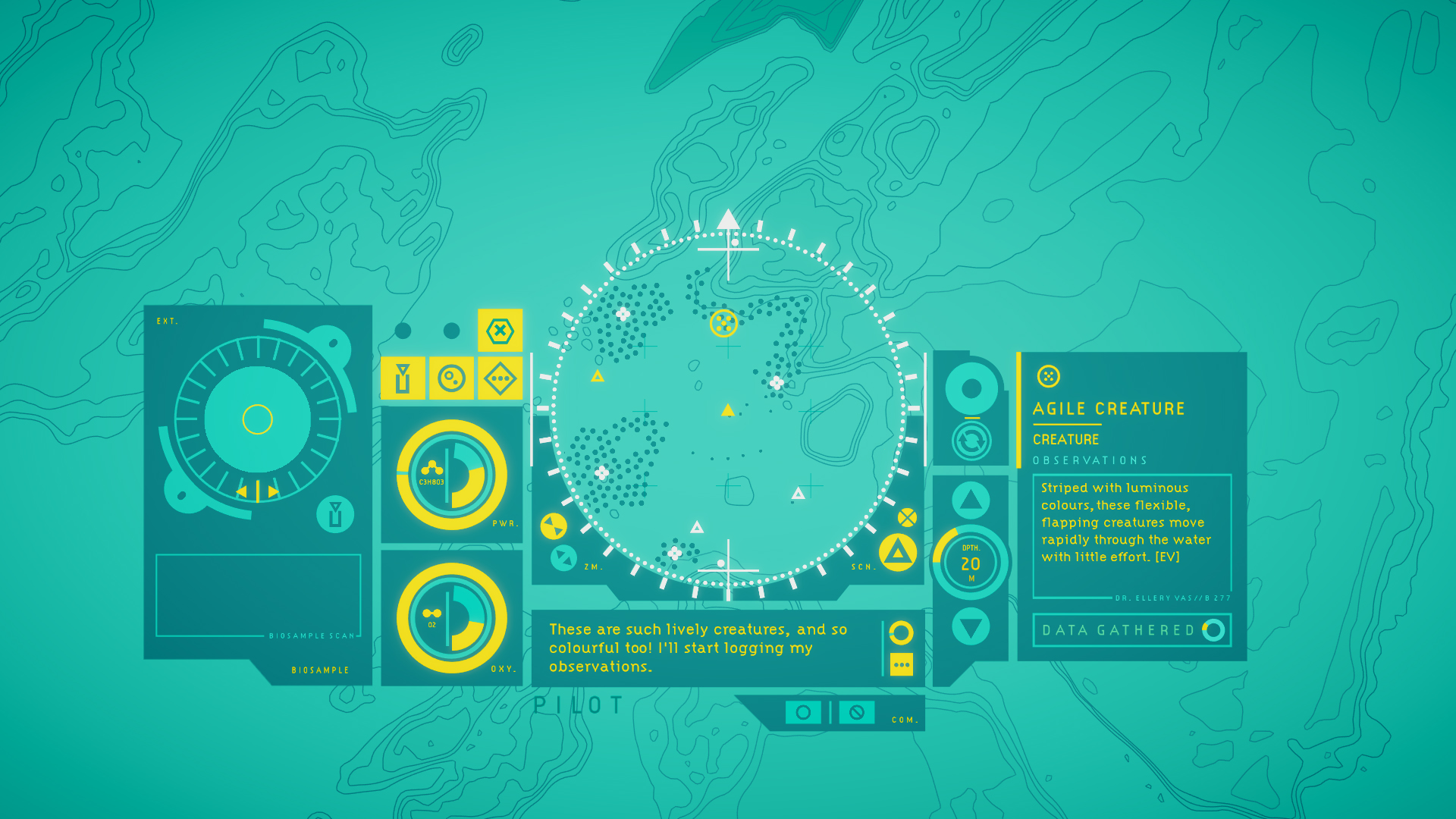

Building an entire game around this unique and somewhat weird perspective would put off many risk-averse indie developers but it’s cleverly managed here by foregrounding the HUD interface and making it the central object of the game. Not only does this define the game’s primary actions of scanning for waypoint markers then setting headings to swim between them, it also reinforces themes of sensing the world through science and the gap between AI and human perception.

With a striking duotone colour palette and geometric blocks overlaid on the backdrop of a beautifully crafted bathymetric map, the interface is reminiscent of experimental Flash websites from the early 2000s and the work of cult 1990s graphic designers like Volumeone, Büro Destruct and The Designers Republic. Instead of visually communicating the intricacy of ocean life on Gliese 667 Cc, the game abstracts it through data readouts, putting a huge emphasis on Ellery’s text narration to convey details about the world.

Given that the game’s structure is basically that of a Metroidvania with the bathymetric map sectioned off into gated zones to be progressively unlocked and explored, this narrative conceit could easily frustrate a lot of players itching to zoom around the coordinate space with thrusters.

The buttoning-down of movement into manual hops between waypoint markers does feel labourious and restrictive at first. You have to slow down to find the rhythm of the game but once it clicks you realise this is the whole point. The gentle pace and evocative sound design helps the game feel contemplative and enhances the sensation of being underwater. The ocean isn’t there as an open world to be consumed. The player as the AI, can only observe, document and learn from it in fragmentary pulses.

While the player dutifully performs the work of sampling and cataloging underwater life, Ellery’s narration shifts from planning science expeditions to unwravelling a dark secret from the planet’s recent past. Through repetitive exploration and observation gradually unlocking more of the world, the narrative begins to feel less like a dialogue between an AI and a human scientist and more like a symbiotic relationship, a shift which becomes pivotal to the climax of the story.

The developing symbiosis between the player and narrator also echoes the patterns of alien life on Gliese 667Cc where there are no clear borders between species and traditional biological concepts of competition and cooperation cannot be easily applied. This speculative worldbuilding draws strongly from the work of radical biologist Lynn Margulis who fought for decades to get the scientific establishment to accept her theories about the role of symbiosis in evolution.

More critically-minded players might find these themes jarring with the game’s emphasis on biological sampling and analysis. Despite the richly detailed symbiotic ecosystems, species are still divided, classified and labelled in boxes reflecting standard videogame patterns for inventory and collections. Processing these samples is fun in the same way as crafting in games like Minecraft or No Man’s Sky, but this skew towards familiarity brings with it the same extractive mentality that In Other Waters works so hard to transcend through its narrative.

This isn’t necessarily a weakness. An important fictional detail is that the equipment to catalogue and colonise exoplanets is provided by the Baikal corporation, fulfilling the standard genre trope of going about its business with an extreme emphasis on resource exploitation and biological domination. While gameplay interactions with the inventory seem to pull away from the game’s themes of symbiosis and holism, this could make still make sense as corporate tech in the context of the story and doesn’t overly constrain the writing.

Many observations that fill the catalogue turn out to be sprawling notes about the problems of trying to classify this life. Some of the samples crash the scanner and are unclassifiable. When the story has concluded and all the content has been unlocked, the ocean still holds mysteries.

In response to the challenge of telling stories during a global systems crisis, novelist and critic James Bradley stresses the need for artists to “move outside of a human frame of reference.”

Many authors in literary and science fiction communities have grappled with this problem, tersely summarised by novelist Jennifer Mills as “all novels are Anthropocene novels,” but this insight hasn’t permeated so deeply into the game development scene as yet.

Meanwhile, gentle aesthetics and nurturing experiences in recent titles like Nintendo’s Animal Crossing: New Horizons have captured the attention of extremely broad audiences as part of an emerging industry trend of gardening games. There are many radical possibilities for gardening games to take the medium to new places and engage with the crisis in new ways, but so far this trend has focused more on fantasies of safety and abundance than ecology.

Such fantasies have a lot to offer in an anxious and stressful time of pandemic lockdowns, economic disruption and climate change. But when the soothing balm of safety and abundance is delivered through representations of cozy capitalism (with fervent racoon landlords and limitless islands to colonise and extract resources from) it tethers us to the human frame of reference, limiting our imagining of possible futures.

The problem of stories being relevant in the time of Coronavirus and climate doom recalls the tension behind Joan Didion’s famous line about the end of the 1960s in America: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” People instinctively want to read this as an affirmation, but Didion was really trying to explore the futility of seeking out meaningful stories in the chaos and confusion of massive change and human brutality.

How can we make sense of a formless global crisis that is so big it has no intrinsic narrative structure or meaning? How can we talk about loss and grief at a personal scale and a planetary scale without being overwhelmed by it? How can we meet our needs for solace and hope without turning away from the more important work of building solidarity and supporting our communities?

Videogames are certainly not a priority in the world right now and there’s no necessary requirement they be artistically motivated or relevant to what’s going on. It’s better they aren’t in some ways. More than ever, we need worlds to escape into that offer us some sense of control, predictability and emotional respite. Even just the feeling of doing something we would normally be doing outside of quarantine helps.

In Other Waters is not a gardening game and doesn’t follow cozy design conventions, yet players are reporting similar calming and gentle experiences happening within a story centred around the grief of ecosystem loss. It feels like it’s building on the ecological storytelling tradition of Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind where science is allied with kindness and curiosity, reframing toxic wastelands as places of hope and new life.

Solidarity might be more important than hope right now, but the future of humanity depends on what we can imagine it to be. In Other Waters hints that this future involves a deep respect for the way life is intrinsic to oceans, sustained through symbiosis and shared existence.

I also came away excited at the possibilities for new videogames that can reintegrate the ancient wisdom of seeing oceans as intricate living seascapes and networks of pathways rather than formless blue grids.

The idea of bearing witness to vast ecological destruction with a gentle soothing tone might have seemed dissonant or contradictory not so long ago. Right now, it feels like a fairly decent expression of our time.

In Other Waters was released April 4 2020 by Fellow Traveller. It’s available for Windows, MacOS and Switch platforms.