Horizons of the New Berlin

As a newcomer to Berlin, one of the things I have noticed more and more is the precarious balance of the inner-city between corporate and community forces. Berlin certainly doesn’t feel like the largest city in Germany. The outer suburbs beyond the ring extend far and wide, and it’s not often that people living in the so-called ‘alternative’ or ‘post-hip’ districts in the central-East side would venture outside of their well trodden blocks.

Berlin is famous for rebuilding itself, largely as an effect of its torturous history, and this construction continues unabated today, perhaps even increasing in its intensity. In this context, gentrification is a confusing and contested term. All over the city, the detritus of construction, boards over the sidewalk and blocked off avenues are as ubiquitous as the Spätkauf and Turkish Döner houses. But the gentrification is something altogether distinct. You can feel its pressing weight on the border of Mitte in Prenzlauer Berg, like a creaking glacier inching from Bernauer Straße towards Schönhauser Allee. Many of the older residents–those who lived through the radically open and exciting times of the 1990s–treat this as inevitable, like the inverse of Ghandi’s formula: Then they win.

Gentrification in Prenzlauer Berg.

But the tension of 2009 Berlin involves so-much more than the investor class renovating residential buildings in their own Mittelschicht image. Far more acute is the large scale encroachment onto the city with the planned delivery of vast complexes that will permanently alter some of the most iconic neighborhoods in the city. In these zones of corporate redevelopment, the juxtaposition of architecture stands-out because it is really the juxtaposition of utterly disparate world-views. Is this too, inevitable?

Not everyone believes so. Berlin’s grime, graffiti, and yin-yang of Eastern and Western architecture is unique in Europe, and the urban layout of the city is strange – unlike most modern cities, it does not have a CBD. You can see tourists walking along the road beyond the famous (and now ruined) East-Side Gallery, not even aware that that shambling wall beside them is one of the most significant icons of the Cold War. While spectacular and a major tourist attraction, the Museumsinsel feels scrappy and half complete. That is part of the beautiful charm of this city, a charm that many Berliners feel strongly about preserving.

Halbfertigem

This organic incompleteness doesn’t sit right with those who have a more polished and standardized vision for this great capital of Europe. While years ago, it was almost a given fact that the Stadtschloss would be rebuilt in a 21st century manner. Right now, it’s all starting to spill over, and the proposal is up against serious opposition. Corruption in the official architecture contest has had embarassing consequences. Perhaps “Private money will make this dream come true.”, but with the announcement of Schloss Mit Lustig!, there is a clear message that this development may have profoundly negative consequences for Berlin’s identity.

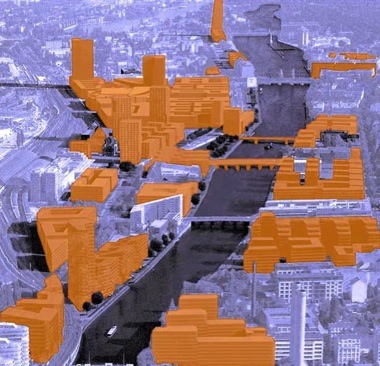

Further down the river, in the border between the Wrangelkiez and Warschauer Straße, there is another deadlock, another grand architectural plan that is half-finished, has not fully come to fruition. The Mediaspree, is harder to pin down because of its shifting scope and aging agenda. What is Mediaspreee? An investment company and charity? A large mixed-use corporate complex along the banks of the river between Friedrichshain and Kreuzberg? An ambitious plan to integrate public and private space?

Criticism of Mediaspree references the rather dangerously ambiguous concept of a “partly privatized urban policy”, and “urban renewal from above”. A large and active protest movement exists. Clearly, the full realization of this plan would smash entire neighborhoods and blocks into the ground.

While for now, these vacant spaces and tumbledown blocks are the backdrop to an era of the city’s development, the future is uncertain.